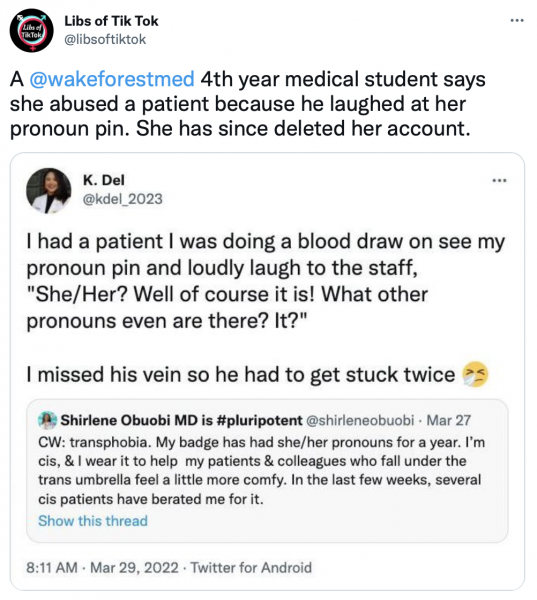

A young physician at Wake Forest recently posted to her Twitter feed that she tortured a patient because he made a comment about her pronoun pin:

To be clear, there is some ambiguity here — it may be that she did not deliberately miss the vein, but was simply pleased that she did. To me, however, that’s a distinction without a difference from an ethical point of view. There are likely those who would claim that this is not “torture” per se, but in fact it is — it is the intentional infliction of pain because of the victim’s ideology. By a physician. Not a lot of pain. And not quite a physician. But close enough for government work, in my personal opinion.

A poster in a discussion group of physicians I belong to was appalled by this and could not understand how a physician would do this, since it is in direct contradiction to traditional medical ethics. But, in fact, it makes perfect sense, and it is a well-documented phenomenon in the torture literature. Those who know me well know that while I was in the military, I did image analysis in cases of forensic pathology interest, and some of those were instances of executions and torture by Islamic jihadists. I became interested in this literature during this time.

The key here is the concept of “dual loyalty.” Jasper Sonntag wrote a great article about this in the journal “Torture” in 2008 (Sonntag J. Doctor’s involvement in torture. Torture 2008 18(3):161-175). He writes:

Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has defined dual loyalty as: “Clinical role conflict between professional duties to a patient and obligations, express or implied, real or perceived, to the interests of a third party such as an employer, insurer or the state.” Various cases of doctors in dual loyalty conflicts have been described, such as doctors in Iraq under the Baathist regime, police doctors in Germany, U.S. military medical personnel in Iraq, Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay, prison doctors in Denmark and Canadian military physicians in Afghanistan.

He continues:

The ethical dilemma of dual loyalty in the war on terror is discussed by Singh:“ If the detainee is being subjected to poor detention conditions or ‘robust interrogation’ by the detaining power, state physicians could experience a conflict of interest between: a) their duty to care for and protect a … detainee … against abusive treatment…; and b) their patriotic duty to protect and serve the interests of their country (which might arguably require the physician to remain silent about such treatment).”

He also describes how “social cicumstances and particular factors” might influence some physicians to lose moral perspective and to facilitate abuse of detainees. These “circumstances and factors” are “ideological totalitarianism”, “moral disengagement” and “victim-blame”. “Ideological totalitarianism” can result from “the negative labeling or devaluing of a group by influential forces”. (emphasis mine)

The Physicians for Human Rights Working Group white paper that Sonntag refers to is also valuable. They write:

Since ancient times, many societies have held healthcare professionals to an ethic of undivided loyalty to the welfare of the patient. Current international codes of ethics generally mandate complete loyalty to patients. The World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Geneva, the modern equivalent of the Hippocratic Oath, asks physicians to pledge that “the health of my patient shall be my first consideration” and to provide medical services in “full technical and moral independence.” The WMA International Code of Medical Ethics states that “a physician shall owe his patients complete loyalty and all the resources of his science.”

In practice, however, health professionals often have obligations to other parties besides their patients – such as family members, employers, insurance companies and governments – that may conflict with undivided devotion to the patient. This phenomenon is dual loyalty, which may be defined as clinical role conflict between professional duties to a patient and obligations, express or implied, real or perceived, to the interests of a third party such as an employer, an insurer or the state.

They continue:

How might a health professional become complicit in a human rights violation? First, when employed by or acting on behalf of the state, health professionals may become agents through which the state commits a violation, for example, by participating in torture of an individual at the behest of state interrogators.

Second, even in private doctor-patient encounters, health professionals can become complicit in violations by adhering to – and thus furthering – state health policies and practices that unjustly discriminate on the basis of race, sex, class, or other prohibited grounds, or that deny equitable access to health care. Where the state has failed to take necessary steps to establish a health system that affords equitable access to health services, the health professional participating in that system has an obligation to press for alternative policies designed to end the violations.

Third, even where no explicit state policy is involved, in circumstances where the health professional engages in cultural or social practices that violate human rights, for example, “virginity examinations” or genital mutilation of women, he or she becomes the vehicle by which the violation is accomplished.

What happened here, in my opinion, is of the third kind — where the medical student performed her act of torture on the basis of her cultural perspective.

This is not really very surprising. Medical practice in the United States has largely embraced dual loyalty in the name of “manged care” and “public health,” and the slippery slope remains as slippery today as it was during the eugenics craze of the early and mid 20th century. Many years ago, when I was in the Army, we had a “bioethicist” come an talk to us. He told us that all us folk who were trained before “modern” medical practice had been trained that we were the patient’s advocate. It was our job to do whatever we could to act in the best interest of our patient and provide him or her the best possible care.

No more, he said. Modern medicine recognized the responsibility of the physician for the “greater good.” In other words, when considering treatment for a patient, we should also consider its impact on society as a whole. Thus, for instance, if an older patient with cancer needed expensive chemotherapy, but that money would be better spend for vaccines (or today, I suppose, gender reassignment surgery) for children, then we should not tell the older patient about that option and deny that care. instead, we should allow our patient to die in order to provide better care for others. This is the fundamental ethic of so-called “managed care.”

And this idea of programmed care with an eye to the utilitarian greater good has, in fact, become the norm, which means that the medical establishment in the United States has put an enthusiastic blessing on divided loyalty in physicians, and is teaching young physicians to place individual patients second to social needs.

Nor should it be surprising that these actions seem so justified to the medical student that she brags about it on social media. Utilitarian ethics commonly devolve into atrocity — the common good justifies anything. As Claudia Card notes in “The Atrocity Paradigm: A Theory of Evil”

The “greater good” justification for harm sets no upper limit to the extremity of harm that any individual might be made to suffer in order to produce benefits for others. This is why the slavery example is so powerful. The problem is not just that slave labor is stolen. People who are enslaved too often have no effective protection against such things as torture, murder, malnutrition, the breakup of their families through sale, and, of course, no freedom to determine the course of their own lives. The utilitarian rationale appealing simply to benefits that outweigh harms seems compatible with letting a few die (or killing them outright) to spare many others a significant but nonfatal hardship…

Contrary to initial appearances, Bentham’s utilitarianism does not clearly give prominence to sufferers. Rather, it gives prominence to suffering, abstracted from the lives of sufferers. Both utilitarian justifications—the “greater good” argument and the “no better alternative” argument—invite us to treat harms and goods as fungible, like money, as though we could interchange their forms with no serious change in value simply by making appropriate adjustments in quantity. Bentham’s calculus, directing one to sum up the harms and benefits done to everyone affected and see where the balance lies, does not distinguish atrocities from lesser harms. By the process he advocates for estimating overall harm, an enormous number of minor harms appear to add up to an atrocity. But often they do not. Robbing millions of people of five dollars each is not worse than conning a retired couple out of their modest life savings. The point is not that numbers don’t matter for an atrocity. Murdering millions is worse than murdering a few. The point is that the concepts “beneficial on the whole” and “least harmful on the whole” are too ambiguous to enable us to identify or rule out atrocities.

Card would not consider what this medical student did an “atrocity” because it was a small evil. However, the process of utilitarian dual-loyalty thinking leading to these kinds of acts is the same. And like most evil, it starts small and grows over time. I cannot understand why anybody is surprised that a modern medical student would take these lessons to heart, or why she would have difficulty in trying to “identify or rule out atrocities.” And, really, you are seeing, in a microcosm, exactly that ethic. The same ethic that has led to “real” substantial medical atrocities repeatedly in the past.

This is a small thing. But great evil in individuals tends to start small. Serial killers start by harming animals. The problem may or may not be with this one student, but it is certainly inherent in the ethic she’s been taught.

Wake Forest has put out a statement that this does not represent its values. But, in my opinion, it does. Precisely, in fact — because that *is* the modern medical ethic.